It used to be that radiation therapy for prostate cancer involved weeks or months of repeat visits to a clinic for treatment. Today that’s not necessarily true. Instead of giving small doses (called fractions) per session until the full plan is completed, radiation delivery is moving toward high-dose fractions that can be given with fewer sessions over shorter durations.

This “hypofractionated” strategy is more convenient for patients, and mounting evidence shows it can be accomplished safely. With one technology called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), patients can finish their treatment plans within a week, as opposed to a month or more. Several devices are available to deliver hypofractionated therapy, so patients may also hear it referred to as CyberKnife or by other brand names.

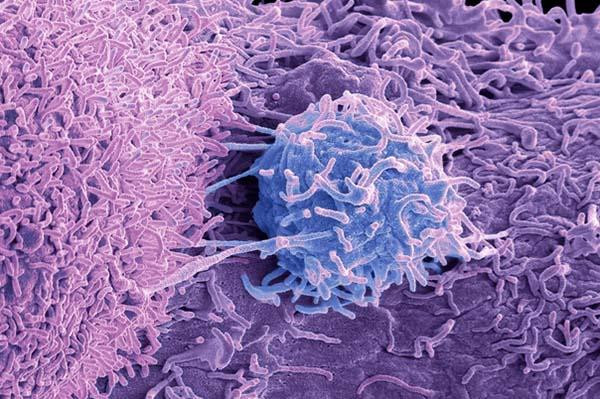

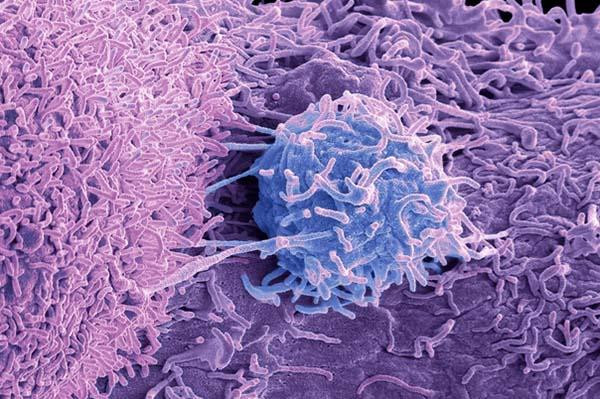

An SBRT session takes about 20 to 30 minutes, and the experience is similar to receiving an x-ray. Often, doctors will first insert small metal pellets shaped like grains of rice into the prostate gland. Called fiducials, these pellets function as markers that help doctors target the tumor more precisely, so that radiation beams avoid healthy tissue. During treatment, a patient lies still while the radiation-delivery machine rotates around his body, administering the therapy.

How good is SBRT at controlling prostate cancer? Results from a randomized controlled clinical trial show that SBRT and conventional radiotherapy offer the same long-term benefits.

How the study was conducted

The trial enrolled 874 men with localized prostate cancer, meaning cancer that is still confined to the prostate gland. The men ranged between 65 and 74 years in age, and all of them had prostate cancer with a low or intermediate risk of further progression. The study randomized each of the men to one of two groups:

- Treatment group: The 433 men in this group each got SBRT at the same daily dose. The treatment plan was completed after five visits given over a span of one to two weeks.

- Control group: The 441 men in this group got conventional radiotherapy over durations ranging from four to 7.5 weeks.

None of the men received additional hormonal therapy, which is a treatment that blocks the prostate cancer–promoting effects of testosterone.

What the study showed

After a median duration of 74 months (roughly six years), the research found little difference in cancer outcomes. Among men in the treatment group, 26 developed visibly recurring prostate cancer, or a spike in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels suggesting that newly-forming tumors were somewhere in the body (this is called a biochemical recurrence). By contrast, 36 men from the control group developed visible cancer or biochemical recurrence. Put another way, 95.8% of men from the SBRT group — and 94.6% of men in the control group — were still free of prostate cancer.

A word of caution

Earlier results published two years into the same study showed higher rates of genitourinary side effects among the SBRT-treated men. Typical genitourinary side effects include inflammatory reactions that increase pain during urination, or that can make men want to urinate more often. Some men develop incontinence or scar tissues that make urination more difficult. In all, 12% of men in the SBRT group experienced genitourinary side effects at two years, compared to 7% of the control subjects.

“Interestingly, patients who were treated with CyberKnife appeared to have lower significant toxicity at two years compared with those treated on other platforms,” said Dr. Nima Aghdam, a radiation oncologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and an instructor of radiation oncology at Harvard Medical School. By five years, the differences in side effects between men treated with SBRT or conventional radiation had disappeared.

The authors advised that men might consider conventional radiation instead of SBRT if they have existing urinary problems before being treated for cancer. Patients with baseline urinary problems are “more likely to have long-term toxic effects,” the authors wrote, adding that the new findings should “allow for better patient selection for SBRT, and more careful counseling.”

“This is an important study that validates what’s becoming a standard practice,” said Dr. Marc Garnick, the Gorman Brothers Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and editor in chief of the Harvard Medical School Guide to Prostate Diseases. “The use of a five-day treatment schedule has been well received by patients who live long distances from a radiation facility, given that treatment can be completed during the weekdays of a single week. As with any cancer treatment choice, the selection of the appropriate patient is crucial to minimize any potential side effects, and this can only be done after a careful consideration of the patient’s other medical conditions.”

“This elegant study will put to rest any questions regarding the validity of SBRT as a standard-of-care option for many patients with prostate cancer,” Dr. Aghdam added. “Importantly in this trial, we see excellent outcomes for many patients who were treated with radiation alone. As this approach gains broad acceptance in radiation oncology practices, it remains critical to carefully consider each patient based on their baseline characteristics, and employ the highest level of quality assurance in delivering large doses of radiation in fewer fractions. As the overall duration of radiation therapy gets shorter, every single treatment becomes that much more important.”

About the Author

Charlie Schmidt, Editor, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases

Charlie Schmidt is an award-winning freelance science writer based in Portland, Maine. In addition to writing for Harvard Health Publishing, Charlie has written for Science magazine, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Environmental Health Perspectives, … See Full Bio View all posts by Charlie Schmidt

About the Reviewer

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Marc B. Garnick is an internationally renowned expert in medical oncology and urologic cancer. A clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, he also maintains an active clinical practice at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical … See Full Bio View all posts by Marc B. Garnick, MD